His parents set him up for failure when they named him Pierre-Auguste Salvatici. Even if he hadn’t grown up with a persistent speech impediment and severe respiratory problems, Pierre-Auguste Salvatici could never live up to the grandiosity of the name. He was small, unable to play any sport except ping pong, and couldn’t swim. He got straight Bs, played no instruments and, in fact, had been officially diagnosed as tone deaf by a former piano teacher after playing an entire song without noticing four of the keys were out of tune. Pierre-Auguste Salvatici had no interesting hobbies, no desire to go to parties, nor any grand aspirations for life. Very little made him stand out from the crowd besides his imposing name, which he always gave in full.

What Pierre-Auguste Salvatici did have was the ability to gather people. No one could really articulate why they were drawn to him. He wasn’t charismatic or attractive or a particularly interesting conversationalist. His stutter frustrated many an impatient person and he eschewed contact with any animal on account of his allergies. But when he started his own club, people clambered to get in. Among those rejected were Amanda Lyn Case, Jennifer F. Ravenswood, and Anders Hjelmstad.

Even though JoJean Jones-Jones had been turned away, Sigmund “Ziggy” Broadhurst convinced Pierre-Auguste Salvatici to let David David Davis join on the condition that people stop calling him “Triple D” because Pierre-Auguste Salvatici did not care for crude humor.

I have to admit that my name had never made me feel particularly special, until Spider, Sequoia, and SweetPea Moondance, a set of triplets born into a hippie commune, pointed out that my parent-given alias was the shortest in the club, and when only using my first initial, my name was B. Short. And Pierre-Auguste Salvatici always called me “B.”

Growing up with a name next in the alphabet to Pierre-Auguste Salvatici meant I was never far from his family’s eccentricities. Perhaps his overt normalcy was in reaction to his parents’ oddness. His mother was a professional archer who taught lessons at a traveling Renaissance Faire. She wore fairy wings over her period dress—even outside of work—and sometimes pointy ears. His father, on the other hand, was covered in tattoos of varying styles, most notably a Japanese koi fish on his neck. Rumor had it that Mr. Salvatici used to rob banks, but now he worked with security companies to find holes in their systems. Some people believed that he still stole from the banks to fund his family’s large home, which was painted an ugly purple.

Along with being neighbors in the alphabet, Pierre-Auguste Salvatici and I were neighbors in the literal sense. The glimpses I got into his bedroom on the rare occasion he opened his curtains taught me very little. He had some books on a small bookshelf, a nightstand with a plain lamp and a notebook, some clothes on the floor, a desk full of homework supplies. No family photos or trinkets or posters.

The ugly purple house is where Pierre-Auguste Salvatici’s club met upon his whims. Though he’d capped the club’s membership at 31—the number of kids in his kindergarten class—a core group of us made it to nearly every meeting. We started with tea served out of a ladybug tea set and a plate of vanilla Oreos. Every time we drank a different tea—Irish breakfast, Sleepy Time, genmaicha, Earl Grey, lapsang souchong—and never iced, even during the 100-degree summer days.

Somehow the teamaking became my duty, as I was usually the first of the club to arrive. Pierre-Auguste Salvatici provided the tea of the day, access to the stove and kettle, and the ladybug tea set. The rest was up to me.

The ritual of teamaking became somewhat calming for me, and I began to look forward to watching Pierre-Auguste Salvatici take a sip and give me his nod of approval.

We gathered in the Salvatici family’s partially finished basement. The floors and walls were still concrete, but the large space had a bathroom, furniture, and rugs in lieu of carpet. Tapestries hung on every inch of wall, some like those you might expect in a medieval castle, others with lotus flowers, and even more were tie-dyed or patched together like quilts. The only windows were the small rectangles near the ceiling that were only there for fire safety. A collection of floor lamps, fairy lights, and fake candles provided the rest of the light.

When we were all seated on rugs or cushions—everyone eschewed the lumpy chairs and loveseat—the talent show would commence.

Pierre-Auguste Salvatici had no special talents, but the people he collected all had at least one talent as strange or amazing as their names. David David Davis, who now went by “3D,” could throw playing cards so fast and accurately he could slice through some fruits. The Moondance triplets could speak eight non-English languages. SweetPea would sing in one or more of these languages while Spider and Sequoia played mandolins. Zdzislaw Pielucha was a pro at the 1998 version of the game Street Fighter. Ziggy Broadhurst could type 200 words per minute.

Sometimes, the talent show was more of a show-and-tell. Basil Berry and Ambrose Strawberry, “The Berries,” restored old music boxes. They would bring something in one meeting, play the broken tune, and then bring it back when it was fixed so we could all listen to the chimes of the Moonlight Sonata or some song from a Disney movie. Ophelia HaHa-Bumps could create near perfect postage stamp forgeries and would make everyone guess which were hers and which were real.

Despite being in Pierre-Auguste Salvatici’s club without a strange name, I also didn’t have any special talent. I was connected with quite a few local musicians due to my job at a local café, and one of my cousins was famous in the opera circuit in Canada, but none of this musical talent touched me. I could play chess poorly and was in an advanced math class. I had a birthmark in the shape of a lima bean on my shoulder. My voice had a slight southern twang because of my father’s Texas origins. None of these things made me stand out. Yet Pierre-Auguste Salvatici continued to invite me to the club meetings, never urging me to “show and tell.”

I began to suspect that Pierre-Auguste Salvatici just needed someone even more average than him around.

So I spent my free time attempting to develop new skills, to at least earn half of my spot in the club. Spider Moondance tried to teach me French, and then German, but I could only remember that the word for lightbulb in German translates to “glow pear.” I played hours of Street Fighter with Zdzislaw Pielucha and read up on antiques restoration. I was not smooth enough to pull off magic tricks, even the simplest ones.

Then I thought that I should try something on my own, something no one else could do. That was the point, after all. Juggling a soccer ball—I tapped out at four. Making the perfect grilled cheese—too relative. Making my own snow globes—glitter everywhere except in an actual snow globe. I even had coworkers teach me how to do latte art, and all I could manage was a lopsided heart.

One day, I sat outside on my porch attempting to fold a piece of paper into a frog and failing on so many levels. My parents’ dog was chewing on a stick, ears pricking up every time and grunted in frustration. I’d just balled up the paper and chucked it at a tree trunk, causing Mister Miyagi to chase after it, when Pierre-Auguste Salvatici walked out of his front door and waved at me. I waved back with a sigh. “Are we meeting today?” I asked him, despite wanting nothing less than to face ten people more interesting than I was.

“N-no meeting.” He pointed at the dog with an uncomfortable expression. “Should he be eating that pa-paper?” Even though he spoke slowly, his stutter still forced its way forward.

Mister Miyagi, a short-legged Shiba Inu, was tearing apart the origami paper and swallowing chunks. I shrugged, figuring it was harmless. He’d eaten stranger things without getting sick—a whole sock, an oatmeal cookie, liquid from a snow globe I’d dropped on the kitchen floor.

Shoulders hunched, Pierre-Auguste Salvatici turned to walk toward his garage when he paused and turned around. “Do you dr-drive?”

I answered in the affirmative, and Pierre-Auguste Salvatici admitted to needing a ride. This somehow led to me offering to be his chauffeur for the day. I led Mister Miyagi inside with a treat and met my neighbor in the garage.

“Where are you going?” I asked as he buckled his seatbelt. He insisted on buckling in before I even started the car. Apparently, carbon monoxide poisoning was a concern if a car was started two seconds too early inside of a garage, even though I’d already opened the garage door and would have backed out right away.

“Pulmonologist.” Pierre-Auguste Salvatici punctuated this announcement with an aptly timed coughing fit. He pulled out his red inhaler but ended up not needing it before his breathing returned to normal.

What Pierre-Auguste Salvatici failed to mention were the four other destinations. After I waited around for almost an hour in a pulmonology clinic’s waiting room, we drove to CVS and waited another 30 minutes for a new asthma medication, which I was surprised to see came in the form of pills. Wasn’t asthma medication supposed to be inhaled directly? Then we got Chipotle, because he wasn’t supposed to take the medication on an empty stomach. The fact that he got meat in his rice bowl surprised me. He struck me as the vegetarian type. But he didn’t want to eat in the restaurant, so we took a pit stop at the park, where he spent more time sneezing and coughing than eating.

And lastly, we went to the library to pick up a book he had on hold.

The librarians had clearly been pulled in by that strange magnetism Pierre-Auguste Salvatici had. The two at the desk waved to him, greeted him by name, and one who was shelving books came over to show him a book.

The two books Pierre-Auguste Salvatici left with were old-fashioned, the kind with no dust jackets and titles in gold lettering on the leather spine, inevitably with a letter or two rubbed off. They were the kind that didn’t have stickers on the side with their Dewey Decimal number, the kind that you usually could only look at if you had access to Special Collections.

When I dropped Pierre-Auguste Salvatici off at his house, I insisted on actually pulling up to his house even though we were next door, because the more I saw him outside of school or his basement, the more fragile he looked. His almost constant cough and his stutter and his thick glasses, his small frame and birdlike appetite, his perpetually hunched shoulders.

“Thanks, B,” he said, waiting for me to put the car fully in park before unbuckling. “I hate driving.”

“You do?” I’d never taken note of how Pierre-Auguste Salvatici got around. Had I ever seen him drive? I’d certainly never seen him riding a bike.

My neighbor nodded and then got out of the car with his books, medicine, and leftovers in tow. I stared at him as he swung open the screen door, held it open with his hip, and unlocked the front door of his house. He waved goodbye before disappearing inside.

The next day, after I’d dragged myself out of bed and into the car, Pierre-Auguste Salvatici’s red inhaler greeted me in the passenger seat. It must have fallen out of his pocket. I decided to give it to him at school, where I was heading to learn how to write with my non-dominant hand from Jennifer F. Ravenswood. She was not in Pierre-Auguste Salvatici’s club, nor was her friend Cocoa Danvers, who was a competitive jump-roper and had tried to get me into speed jumping. Instead, I went home and watched Jump In! and admired Keke Palmer’s fast feet.

The red inhaler insisted on my vigilance in looking for its owner, but Pierre-Auguste Salvatici did not attend school that day. In fact, he did not leave his bed that day.

Despite never smoking a day in his life, Pierre-Auguste Salvatici suffered from chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Non-smokers with COPD sometimes have an alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency to blame. A rare genetic disorder.

But Pierre-Auguste Salvatici didn’t even have a negative quirk to make him special. The blood tests had proven that. No, Pierre-Auguste Salvatici was just one of the more than 23 million minors in the United States who were victims of secondhand smoke.

All of this I learned when attempting to return the red inhaler and instead got sidelined by his very talkative and oddly dressed mother.

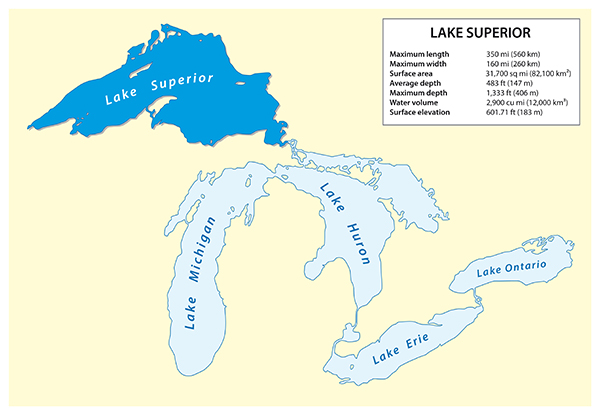

The corner of Pierre-Auguste Salvatici’s room that was hidden from view of my own bedroom contained the hidden parts of the room’s owner. Bed covers in a deep blue, stacks of musty old books including the two borrowed from the library, different types of breathing treatments and inhalers all around, binders and folders full of paper ephemera—old and new—and maps of all five Great Lakes on the walls with pushpins in them.

The books bore titles like The Night the Fitz Went Down or If We Make It ‘til Daylight. The binders were full of copies of old ship logs, newspaper clippings of shipwrecks that occurred on the Great Lakes, more maps, and cargo inventories.

At the center of this strange shrine to Great Lakes shipwrecks sat a boy coughing so loudly that the sound filled the otherwise unobtrusive room. After a couple restarts and some water, Pierre-Auguste Salvatici began to speak in wheezing voice.

“My p-parents gave me two things,” he said without prompting. I set the red inhaler down on top of a stack of books and pulled his desk chair over. As if on cue, he began to cough again. When his breathing returned to as normal as it had been, Pierre-Auguste Salvatici continued. “Bad lungs and a new f-f-family.”

Maybe his sickness had lowered his inhibitions, because Pierre-Auguste Salvatici spoke more than I’d ever heard him do. He stumbled and coughed through his past like he’d been itching to tell somebody but wanted to remain, well, Pierre-Auguste Salvatici.

~ ~ ~

Peter and Augusta were not good parents. They loved their son in theory, but they didn’t take good care of him. The trio always lived near the docks, not always in the same city, but always on the American side of Lake Superior.

Augusta played guitar in a punk band and spent much of her time touring the Midwest. Peter worked on a poorly supervised cargo ship and often smoked cigars to ease the stress of being a single parent half the time.

Rules on the cargo ship were lax. Workers often had family on the boat, especially those who could not afford childcare, and Pierre-Auguste was often one of those children. Toxic fumes from the unregulated boat and the cigar smoke seeped into Pierre-Auguste’s lungs and clung on.

He hated being on the cargo ship. Except when he knew it was ferrying him across the lake to one of his parents’ friends’ houses. These mini vacations were Pierre-Auguste’s favorite days. All of his parents’ friends were strange and interesting, and he loved watching them do strange and interesting things. Like the magician who could breathe fire. Or the two contortionists who could fold themselves inside of a suitcase. But his favorite people to visit were the archer and her heavily tattooed partner.

Though it was fun to watch the archer split an arrow with another arrow from yards away, he mostly loved watching how stable their life seemed. They were always in the same house. The tattooed guy would cook dinner every night. They didn’t make their beds and there were neatly hung family photos on the walls.

Peter and Augusta sometimes left their son with these friends so they could take a break from being parents. They took the cargo ship back to whichever city they were calling home and lived their lives without a child there. These separations became more and more frequent as their son became more and more sickly.

During one of these separations, Pierre-Auguste became sick with pneumonia and ended up in the hospital. When his parents finally showed up, he was already out of the hospital, and Pierre-Auguste found himself hating the two people who had failed to raise him properly. And he made this clear to them.

Peter and Augusta did not much care that their son hated them. Before this era of mutual dislike either ended or became permanent, the cargo ship sank in the middle of Lake Superior. Or maybe on one side. Because the ship was not formally recognized by the government or any legitimate company, no efforts were made to recover the ship or the bodies.

The archer and the tattooed man adopted Pierre-Auguste a year later, when he was eleven years old, and the newly formed family moved to an entirely new state. But Pierre-Auguste’s mind never left the Great Lakes. In his efforts to figure out where his parents may have died, he discovered the surprisingly long list of shipwrecks on the Great Lakes and a penchant for maritime research.

~ ~ ~

Even after this long story, one thing was still unclear. “Why don’t you show this to anyone?” The amount of information Pierre-Auguste Salvatici had dug up was amazing. He’d created his own mini archive in the corner of his bedroom. It must have taken years of extra effort to collect this much, and so much of that must have been difficult to discover. Yet we always gathered in the basement, where our host celebrated everyone else’s talents and kept his own hidden.

“I d-don’t want to be the center of attention f-f-for something so n-negative.” That strange Pierre-Auguste Salvatici charm appeared even in this moment.

“But at least it’s something.” My jealousy spilled out even as Pierre-Auguste Salvatici lay in bed, unable to breathe properly and recounting his worst memories.

Before I had the chance to take back my words or ask more questions, Pierre-Auguste Salvatici spoke again while settling back into his pillows. “Would you m-mind making me some tea? You always make the perfect cup of tea.”

My spine straightened. “I do?”

He nodded.

“What kind do you want?”

Pierre-Auguste Savage smiled like he always did before a club meeting, as if in anticipation of something amazing. “You pick.”

–Ryn Baginski

Sources:

Lung Diseases:

I liked that B find their special talent – making the perfect cup of tea. Great writing – very captivating and engaging story.

LikeLike