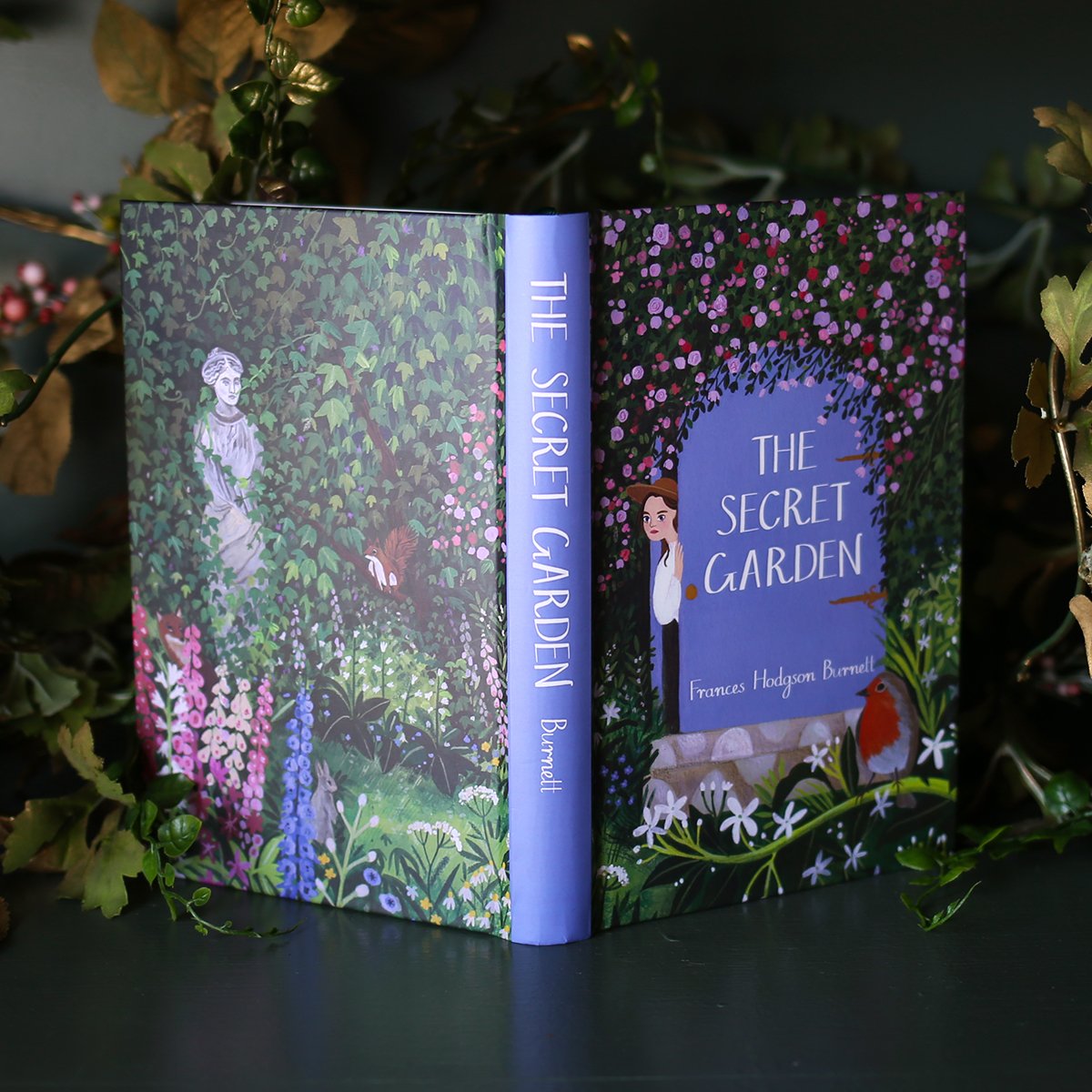

I don’t have a great memory, but one that has stuck with me is the first time I consciously encountered the word “queer.” Young Ryn was under their floral covers, propped up on two pillows, and talking to their dad about the best part of their day. On their lap was an open book they’d just been reading. After mentioning the best of their day—maybe it was a good breakfast, or a compliment from a teacher, or perhaps that moment right before their dad came in—the conversation turned to what Ryn was reading: The Secret Garden.

“I learned what the word ‘queer’ means,” Young Ryn mentioned.

With a slightly panicked look, their dad asked, “And what does it mean?”

“Weird,” Ryn answered confidently, proud of their use of context clues.

Now, Older Ryn understands the panic on his dad’s face. “Queer” was (and still is) used as a derogatory term for people in the LGBTQ+ community. Not a word you want your tween child learning about. However, this memory is one I’ve gone back to as an adult who has figured out and accepted their own queer identity and is okay identifying with that word.

Most queer people have moments they look back on and think, “how did I not know I was queer?” For example, I went through a phase in high school in which I would wear shorts under sagging pajama pants, inadvertently mimicking dudes who wore baggy pants that made their boxers visible. There was also the time I tried on shorts from the “boys” section at the store, and when my mom pointed out that they made me look masculine, I couldn’t figure out why someone might consider that a problem.

This early encounter with the word “queer” is adjacent to those moments, in that it doesn’t really indicate any sign of being non-cishet, but it is one that has taken on a new meaning as I’ve grown up.

Recently, I had the chance to get a copy of The Secret Garden for free and promptly re-read it to see if I could figure out why “queer” is the word I remember learning from a book. And it’s no wonder that’s the one I wanted to figure out! The word “queer” is used as a word for “strange” or “peculiar” almost every other page in The Secret Garden. Sometimes, being “queer” is a point of pride or individuality in the book. Other times, it’s a negative trait that needs to be changed, like the “quite contrary” Mary who has to learn how to respect other people.

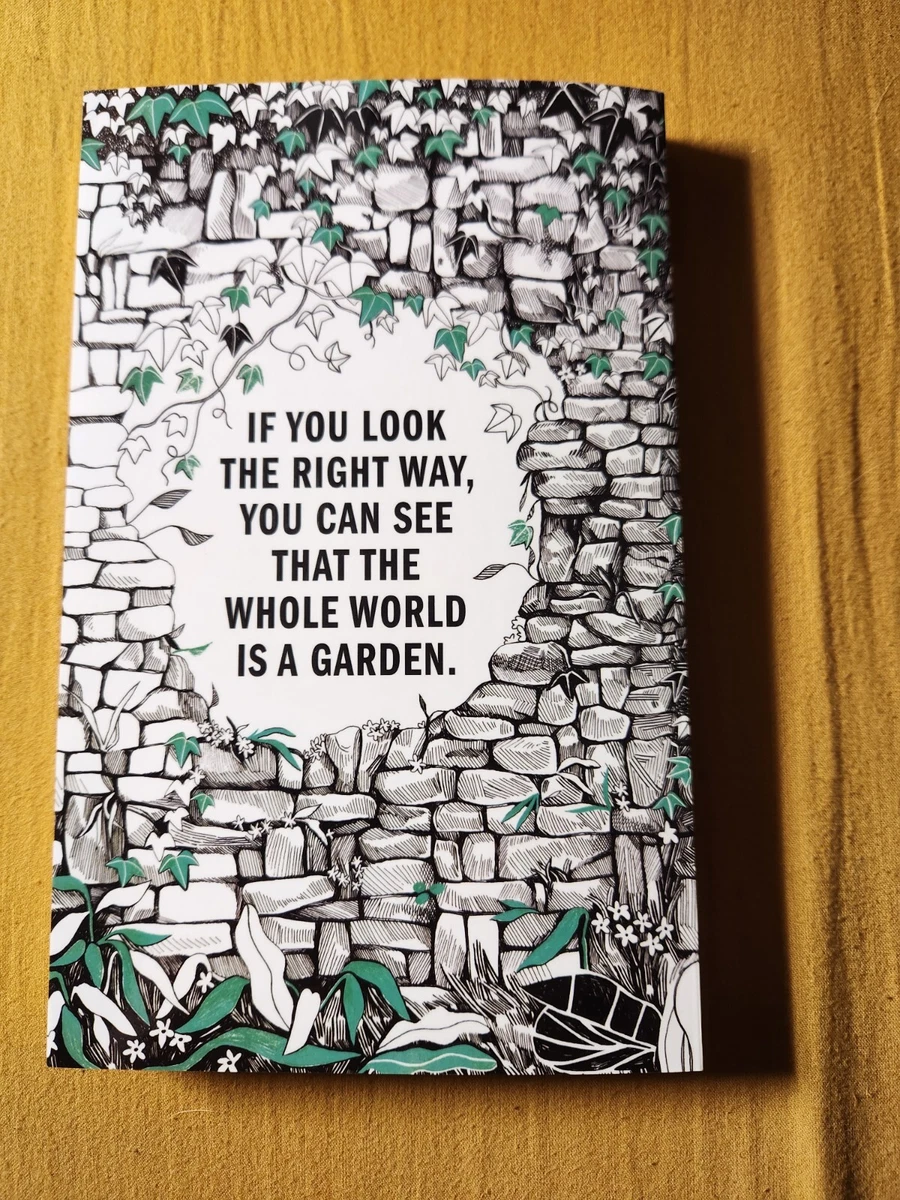

One thing that stood out to me on this re-read is that the “queer” people in the book end up forming a community. The grumpy gardener, the depressed son who is neglected by his father, the girl who feels unwanted by everyone, the boy who seems to be able to commune with nature, and a bird that likes to hang out with people. They all eventually find each other, talk about their weirdnesses, and help each other see that there are good things in the world. All of them are lonely until they find other “queer” people who are willing to look past their quirks, and even celebrate those quirks if they’re not self-destructive. In short, this is one of the first found family stories I fell in love with.

Of course, there are many issues with The Secret Garden: the blatant racism that comes from being written during Britain’s colonization of India, the easy curing of depression and physical issues, the fetishization of poverty by those with money.

But it’s still a children’s classic I would recommend. It’s just… delightful. It feels like spring wrapped up in a story. Children help other children to see how good the world can be despite poor upbringings. They help adults find joy again. They build a beautiful world around each other.

Like nontraditional gardening and children’s rights, the word “queer” has an interesting and not entirely documented history. The word, which is of “uncertain origin,” used to mean “odd” or “unusual,” as in The Secret Garden. However, in 1894, the word was used as a slur against Oscar Wilde (referring to him and his lover as “snob queers,” which sounds like a great name for a queer punk band) during his very public sodomy trial. After this, newspapers began to use it as a slur against men who were attracted to men. Then it became a word for everyone in the LGBTQ+ community, people seen as outside of the norm in our cis-het normative society.

Of course, the word’s history is much more complicated than this short summary (involving the AIDS epidemic, the 1960s civil rights movement, etc.) and the meaning of the word continues to change. But the fact of the matter is this: it’s just a word, until it’s used as a weapon.

As much as I don’t think being part of the LGBTQ+ community should be seen as “strange,” I kind of like being a weird person. I am more than happy to call myself queer and be a part of the queer community. However, “queer” immediately becomes harmful to me when used as a noun. For others, it’s the word itself that hurts, regardless of context.

So as I re-read The Secret Garden, I found myself relating to the main characters both loving and hating their queerness. It makes life more difficult to be different, but it can also enrich your experiences. For example, Mary, who used to hate when boys would sing the “Mistress Mary, Quite Contrary” song to make fun of her, eventually uses the flowers mentioned in the song to adorn the garden, reclaiming the song in a different context and a different moment.

The words people use against us have tremendous power. Sometimes, we can shift that power in our favor. And maybe plant some (physical or metaphorical) flowers along the way.

–Ryn PB