Ernest Kowalski just wanted to pick up some potatoes for his pierogis, but Ziggy’s market was closed on Sundays. Two of his daughters and their kids were coming for dinner that night, so after Mass he’d ventured out to the big supermarket—Walmart.

He hated it. Everything was impersonal and streamlined, but he’d already been waiting in line for five minutes. Only two cashiers were working even though the numbers above the registers went up to eleven—ridiculous. Ziggy’s had two check-out counters, so there were always two cashiers on hand. No false impressions, no space wasted. Ziggy’s daughter Ala and the local boy Frank were lovely young people and top-notch cashiers, always there when Ernie did his weekly shopping on Wednesday. Just three days ago, Ala helped him tweak the amount of seasoning for his pierogis—more pepper, less salt, add nutmeg—which he would be trying today. If he ever got to the cash register.

The woman in front of him who had slowly unpacked an entire cartful of groceries finally reached the card reader. Ernie sighed in relief and plopped his bag of potatoes onto the conveyor belt. He flexed his stiff fingers while the woman searched for her credit card in the depths of her large purse—why did women need purses that big for a trip to the supermarket? Ernie’s wife had kept everything she’d ever needed in a small, black bag that slung neatly across her chest. The woman fished out a wallet twice the size of Ernie’s, and at long last, Ernie approached the cashier—a young woman with dark hair cut boyishly short and a smile that exposed a row of nearly straight teeth. With a slight pang of annoyance, Ernie smiled back. He couldn’t be rude to her just because big-purse lady had miffed him. In fact, this cashier was his favorite person in the whole supermarket—she would send him home with what he needed.

Ernie wanted to get out of this place with concrete floors and beige walls. It felt more like a warehouse than a welcoming store.

“Hello, sir. How are you today?” The cashier smiled wider and looked straight into his face. Ernie thought she seemed genuinely happy. He hadn’t seen a happy worker in the whole store—all that fake enthusiasm.

“Just fine,” he grumbled. Ernie didn’t feel like a grumpy old man, but he sure sounded like one. He began to wonder if his own father hadn’t been so mean after all—just old. Ernie cleared his throat, but paused mid-breath. He heard his wife’s voice whispering in his ear, “Do you see that girl? She looks Polish. Look at her beautiful features. That girl must be Polish.” His wife used to say this often, and she was usually right. He could see no reason to doubt her now that her body lay underground, so he asked the cashier, “Are you Polish?” He squinted at the girl’s nametag: Kitty. Cashier.

Ernie’s gaze shifted from Kitty’s nametag to her face. She pressed her lips together and scanned the potatoes, the loud boop startling Ernie. “Yes,” she answered. “How did your wife know?”

Ernie instinctively glanced behind him, where he always felt his wife walking. She used to walk right on his heel, flat-tiring him nearly every day. None of his shoes had an intact heel. He felt her presence behind him. But no one stood there—not another customer, not a lost child, not his wife. Ernie bristled, and as he was about to slam down a twenty-dollar bill, the bill slipped out of his hand and fluttered down in front of Kitty. Ernie felt like she was playing a prank on him, though he couldn’t imagine how she would know about his wife.

“Do you know one of the kids who works at Ziggy’s?” he asked, this time grumbling on purpose. Maybe there was a social group of young cashiers who traded stories about crazy customers.

Kitty didn’t seem to notice Ernie’s harsh tone. Two slender fingers with several silver rings plucked the money from the scanner. One ring had an eye on it. Ernie thought it looked like those pictures of Egyptian hieroglyphs he’d seen years ago at the university. She said, “No, but I—did you need nutmeg for your pierogis?”

Ernie thought for a moment, attempting to recall a picture of his spice drawer. He couldn’t remember. “I suppose I should get some just in case.” Grumble. Grumble. Ernie’s fingertips began to shake, something that hadn’t happened since his wife died.

“Wait a moment.” Kitty took a deep breath and cocked her head toward Ernie as if listening to someone speak softly. A slight pressure appeared on Ernie’s shoulder, like a hand. He jumped and looked behind him, seeing no one. These chain supermarkets made you go crazy. It must be the ridiculously cold air. And this insolent cashier! Playing with an old man’s mind.

As Kitty opened her mouth to speak, Ernie rubbed the scab on his chin where he’d nicked himself while shaving two days ago. His eye doctor told him he needed bifocals, but they were overpriced. Everyone tried to pull a fast one on an old man. “Please, I would just like to pay and go. I’ll get the nutmeg from a neighbor,” he interrupted.

Kitty pressed a button, causing a drawer to slam open. The clicking noises from the drawer and the clanging of coins grated on Ernie’s eardrums as she retrieved his change. As she handed him the cash, she shut the drawer with her hip. “Of course, sir. And you won’t need the nutmeg. Don’t worry.”

Then a small machine emitted a whirring noise, and a receipt printed about a mile long. What a waste of paper for one item. Just as Ernie was about to snatch the receipt from her hand, Kitty turned toward another printer—one that had just beeped. And out came some coupons. She turned to hand them over. “I don’t need those. I won’t be back.”

After getting home from the store that day, he’d checked his spice drawer and found just the right amount of nutmeg left for his recipe. His pierogis were a hit, even with his picky grandkids. Nutmeg was a new addition to his recipe; how could Kitty have known he would need it? What an odd coincidence. For a month, Ernie could think of nothing other than this young lady. In that one conversation, Kitty seemed to know more about him than Ala and Frank did. They were kind young kids but never learned more about him than his grocery preferences at Ziggy’s. Ernie could not figure out this girl, her exquisite intuition, her sparkling kindness. Most of the young Walmart workers were surly or bored, frowning or yawning in his face. Kitty hadn’t bristled, yawned, scowled, or reacted at all to his grumpiness.

When Ernie’s daughter Addie, his youngest and furthest away, came home to visit, she needed something from the supermarket. Ernie offered to tag along, but almost reconsidered after she told him what she needed—some feminine hygiene product. She seemed to find it amusing that he’d recoiled at the thought of a period. Instead of bowing out, he scowled at the red tulip tattooed on her shoulder and snatched up the car keys.

When they entered the store in a blast of cold air, Ernie didn’t want to seem creepy, so he resisted the urge to peek at the cashiers—three today. He hadn’t admitted to Addie that he’d only tagged along to talk to a specific cashier again—a psychic cashier—because she would just write it off as Old Man Craziness.

After Addie got her feminine products—Ernie still couldn’t say the word tampon—she dragged him over to the self-checkout lanes. Ernie protested. Why should he do someone else’s job? He’d always wanted to keep busy when he worked as a young man. Addie did not budge, but she made no protest when he wandered off toward the cashiers. And on lane 6, Kitty’s smile greeted him. He hung back while she finished up with her customer—a good-looking young man buying some chewy candy to rot his teeth. Kitty held a hand out to Ernie. “Hello, Mr. Kowalski. How are you today?”

Ernie shook her hand, embarrassed at the unsteadiness of his own. “I’m okay. My daughter’s in town.”

The cashier glanced past his shoulder. “Is that her back there?” She pointed toward Addie, who was sitting on a bench near the bathroom. Addie hadn’t even bothered to look for him before taking a phone call.

“Yes. Addie, my youngest. She lives on the West Coast. Too far away.” Addie had moved away for college and never came back to Niles for longer than a week. His other daughters had never left, and he liked it that way. Ernie himself didn’t like to venture too far from his neighborhood. He remembered a time when he could hear Polish and English being spoken up and down the street as they sat out on the porch of his humble brown house. Now the Polish had nearly disappeared, except at church.

Though he was glad to have her at home, Addie had been acting strange on this visit. She would come into a room, apparently ready to talk, and then just sit down silently. He suspected Addie was hiding something from him, and her distance from home had made it easier for her to keep up the secrecy.

Right after he thought this, Kitty leaned forward, a strange gleam in her eye—though he thought that might be the flickering light to the left of them. “Your wife is there on the bench. With Addie. I think Addie is talking to someone named Jack? Jake? Anyway, your wife approves. Addie is hiding the engagement ring.”

Ernie staggered back, unable to shake the feeling that Kitty had read his mind. Addie had been an accidental child, she was much younger than her other siblings, only in her early thirties. The only one not married. Before Ernie’s brain quite caught up to this information, Kitty squeezed Ernie’s hand and said, “I have a customer. See you later, Mr. Kowalski.” Ernie wanted to question Kitty further, to ask her if Addie had been talking to her earlier. Surely, she couldn’t just know these things from intuition. But the woman waiting behind him was tapping her claw-like nails on the conveyor belt, so Ernie motioned to his daughter to follow him out of the store.

Once they were in the car—the tiny Camry that his wife used to hate driving—he asked Addie about getting married. She didn’t seem too startled that Ernie had figured out her secret. She simply said, “I’ve been wanting to tell you.” He noticed she was pulling at a hangnail, a habit he thought she had overcome. “Jane got me an awesome ring. I think you’ll like it.”

“Jane?” Ernie said, startled at the female name. To hide his surprise, he asked her about the proposal. Maybe he’d just heard wrong.

As Addie rambled about how Jane had proposed—“at the art museum, near my favorite painting”—Ernie realized that Addie must have been bursting to tell him. Although he had his reservations about his daughter’s choice of life partner, when he noticed the grin on her face, he supposed Jane couldn’t be much different than Jack or Jake. It would just take some getting used to. He rested his hand on her arm and said, “I’m looking forward to meeting her.”

Addie left a week later, having promised to bring Jane soon to meet Ernie. Ernie was surprised to find himself looking forward to the visit.

After two weeks of pointless supermarket visits, after “Mr. Kowalski” became “Ernie,” the question he’d wanted to ask since their first interaction burst from his mouth. “How do you know these things, young lady? How do you know my wife?”

Kitty, for the first time, frowned. She glanced down, her dark hair hiding her eyes, as she retrieved his change. “I’ve only known your wife in death. It’s how I know most of those around me.” Kitty dropped the coins into his shaky hand, which hadn’t stilled since his first trip to Walmart. She seemed unwilling to look into his eye while he doubted her.

The coins clanked into Ernie’s pocket. “Are you trying to convince me you talk to the dead?” Ernie wondered if it was Kitty who should be worried about her sanity, not him. Communing with the dead was tantamount to black magic, a heresy. He considered referring her to his church.

“Oh, yes. My mom can, too.” Kitty didn’t seem to be joking. Either she was a good liar, or she believed what she was saying. Or maybe his wife really was standing behind him.

“What does she look like?” he asked. This would be the real test of her truthfulness. Although, even if Kitty was lying, Ernie wasn’t sure he could handle it if she said his wife still looked like that decimated body he’d lived with for two years. The afterlife must be more forgiving than that, surely. God wouldn’t do that to her, not such a kind and understanding woman.

Ernie was startled to see Kitty’s teeth flash again, her eyes flickering toward the space behind his left shoulder. Every time she interacted with his wife’s spirit, she seemed even more content, like she was going into a happier realm. Perhaps that’s where her constant smile came from. “She is young, and pale blonde, and wearing her favorite Sunday dress. The one with the lace she sewed to the ends of the sleeves. She’s beautiful.” Kitty fidgeted with the eye-shaped ring on her finger as she spoke.

Ernie knew the dress—green fabric, white lace, and black Mary Janes. His wife had been a beauty, and so had her soul. The only way Kitty could know this was if she saw the picture of his wife he kept on his nightstand, or if she really could see her spirit. He wasn’t sure what to say, how to respond—his thoughts were all jumbled up.

Just as he was about to convince himself again that Kitty was merely pulling his leg, she said, “Have a wonderful day, Ernie. I hope you have a good time at the park. Let me know how your book is next time you come in.”

“I will.” Ernie bristled at her uncanny knowledge of his future plans. He’d never put much thought into his beliefs about clairvoyance, but he knew, without Kitty telling him so, that his wife wouldn’t have wanted him to doubt.

At the park, he read distractedly, taking in very few words at a time. Eventually, he gave up and watched the activity. A bird chirped in the tree beside him. A small beagle clambered after two frantic squirrels. A family of three ate a picnic lunch on an army green blanket that clashed oddly with the fresh green grass. Four teenagers rode bikes down the sidewalk in front of him, laughing at some joke Ernie couldn’t hear. One of them waved. Ernie squinted. It was Frank, one of the regular cashiers at Ziggy’s. Ernie waved back, and Frank stopped as his friends rode on. “Mr. Kowalski, where’ve you been? Ala and I were thinking something happened to you. And Mr. Ziggy’s pretty bummed about losing his best customer.”

Ernie shrugged guiltily, because even as he’d been trying to read and enjoy being outside in the park, he’d been thinking of Kitty and his wife. He shouldn’t have abandoned Ziggy’s, a place that had never let him down, that had won his respect over thirty years of patronage. “I’ve been visiting a friend. But you’ll see me there this Wednesday, young man.”

“Awesome, I’ll see you there, Mr. Kowalski. Enjoy the nice weather!” And Frank was off. What a nice young boy. He was much taller and lankier than Ernie had ever been, but the boy’s mother assured Ernie that Frank ate enough for two.

On Wednesday, Ernie visited Ziggy’s market to do his normal shopping, spoke with Ala about her college scholarship, and let Ziggy inform him about the latest neighborhood gossip. As he browsed the familiar aisles—half the size of the aisles at Walmart—Ziggy gave Ernie an earful about loyalty and sticking with tradition, making Ernie feel even worse about abandoning his friend. The fluorescent lighting seemed dimmer than usual, and the checkout counter didn’t move like the conveyor belts, but Ziggy’s still had the best Polish spices. Frank helped Ernie out to his car, chatting mindlessly the whole time.

Ziggy’s usually gave Ernie a sense of pride in his Polish ancestry, in his neighborhood, in the youth of today. But the shopping trip was less satisfactory than usual. He felt he’d made the trip without his wife. Ernie had gotten used to her presence. So when he got home and realized he’d forgotten cilantro, he drove to Walmart instead.

He didn’t see Kitty at the cash registers and felt ridiculous for driving all this way. Ernie paced in front of the checkout lanes for five whole minutes, mumbling to himself about cilantro and clairvoyance and his wife. He shouldn’t have expected the girl to work every day, and surely she would think his behavior was odd. Then another young lady—Nithali. Cashier—wandered toward the end of her lane and peeked around the magazine display to address the crazy old man. “Sir, I can help you down here,” she said.

Ernie blinked for a long moment. “Oh, yes, of course. Thank you.”

The young lady was nice, helpful, and didn’t get upset when he grumbled, but Ernie couldn’t shake the unsettled feeling that had taken hold of him. Ernie felt as he did the first day he came—he didn’t belong here. He belonged at Ziggy’s. He left through the automatic sliding doors with the resolution to keep his shopping adventures limited to one store, the only store that had served him for years.

Another month passed, and Ernie gazed at the picture of his wife in her green Sunday dress every day. He missed her. And not just her old presence, her living one, but her new presence, too. He visited the cemetery, but a gravestone didn’t quite do the trick. He still teared up at the sight of his wife’s name on the stone.

The same day he went to her grave, his phone rang. His phone was old, still connected to the wall by a curly cord, so answering it meant getting up and trudging into the kitchen. “Hello?” he nearly growled into the receiver. Addie and Jane were on the other end. Although he hadn’t wanted to meet Jane over the phone—technology made everything too impersonal—Ernie pulled up a chair from the table and sat down to chat with the couple. Jane spoke almost fluent Polish to him; she had studied in Kraków for two years. Ernie’s own Polish was rusty. It had always pained him that his daughters hadn’t learned to speak the language, but as he listened to Jane, he hoped she might teach Addie.

“Has Addie shown you the pictures of my church?” Ernie asked in English, hoping they’d been won over by its stained-glass windows and handcrafted pews. They even offered a Mass in Polish for the traditionalists. He and his wife had gotten married in that church, a small gathering with close family and friends in the neighborhood. They’d had the reception in the backyard of their house, and Ernie and his wife had cooked all the food.

“Yes, and it’s beautiful, Ernie, but…” He heard the hesitation in Jane’s voice and shifted in the hard wooden chair.

“We already have everything planned for here,” Addie finished for Jane. Ernie knew exactly what look Addie was giving her fiancée—eyes rolled, eyebrows raised, wrinkles on her forehead. He’d already tried to convince her to come back for the wedding, but she’d remained adamant about staying on the coast.

“I suppose an expensive plane ride is in my future,” he said, accidentally letting his exasperation slip into his tone. Ernie merely wanted his daughter to connect more to the heritage she seemed to be running from.

Jane’s tinkling laugh rubbed uncomfortably against Ernie’s annoyance. “How about this? We keep the wedding here, but Addie and I promise to come visit beforehand. That way we all have to pay for expensive plane tickets.”

Ernie had to admit that meeting Jane in person before the wedding sounded appealing. He wanted to see what she looked like, if her expression was as happy as her voice, if she was taller or shorter than Addie, if she would get along with his other daughters. “Okay,” he agreed.

“Oh, you should make Mom’s chocolate budyń,” Addie suggested, giving Ernie the sneaking suspicion that she wanted to visit just for his cooking. She’d loved eating the budyń as a child. Ernie supposed that this was as good of a return to Addie’s heritage as he was going to get. And maybe Kitty could get his wife to tell him the secret to her recipe.

As he agreed to make them an entire traditional Polish meal, he tried to shake off the thought that he really could commune with his wife. It unsettled him that the thought had come so naturally. The two women signed off shortly after, promising to talk again soon.

A few days after Addie’s call, Ernie convinced himself he needed to buy something on a Sunday, so he drove down to Walmart and searched for some apples. He had some at home, but this supermarket had more types of apples than Ziggy’s, and Ernie felt like trying something new. After some mental math, Ernie decided that the mesh bag of Fuji apples would be cheaper per apple and headed to check out, humming an old tune from his childhood.

He peered over the displays at the end of each lane, all the way up until number eleven, but he saw no one with short dark hair. Kitty still wasn’t there, and he didn’t feel a hand on his shoulder. Ernie was alone. He wandered to the self-checkout, feeling silly for driving all the way here for apples even though he had some at home. A frivolous waste of money, but he bought them anyway to make his trip seem worthwhile. The self-checkout shouted at him the price of the apples, and it took him a moment to figure out where to insert his cash. Then the change clanked in the small bowl and his receipt printed from the machine. He trudged back to his car, frowning even as a supermarket employee smiled back and told him to have a great day. He thought they should all think of their own adjectives. Kitty never used the same one—fantastic, super, lucky, relaxing. Never “great” or “good.”

This became Ernie’s daily routine. He convinced himself he needed something that Ziggy’s didn’t sell, and he ended up with a pile of junk on his countertop—a new can opener, a potato peeler, a short novel he never intended to read, a bag of mints, some batteries, containers that supposedly kept food fresh longer, new table cloths, and a new type of salad dressing he thought sounded tasty. But the pile of junk merely reminded him of his wife’s absence, and as he sat on his bed gazing at her in her Sunday dress, he realized he had become a crazy old man. He’d become that old person that young people make fun of or call “cute.” Ernie didn’t want to be “cute.” He’d lived a full life. He was a father, a husband, a cook—not just a crazy old man.

Still, Ernie couldn’t seem to help himself. The pile of junk grew and grew along with his disappointment. He tried to gather the courage to ask a manager where Kitty was, but he thought he would sound creepy and didn’t want to get kicked out of the store. He felt his wallet getting lighter day by day, and his longing for his wife increased with each item added to the pile on his counter. At least he’d used the salad dressing.

After two and a half weeks of squandering money, Ernie walked into the store and heard, “Hello, Ernie! Long time, no see!” Ernie peeked cautiously over at cash register number seven, hoping he hadn’t started to hear voices. He’d always feared that if he did go insane, his daughters would check him into an institution, because none of them had enough free time to take care of him like he’d taken care of his own parents.

Ernie peered down the row of cash registers and saw Kitty talking to a lady with a huge package of paper towels. Kitty waved at him. Trying not to look too relieved, Ernie took a water bottle from a refrigerator and walked up to her register with a smile. “Where have you been?” he inquired, wincing at the gruffness in his voice.

“Oh, my mother took me on a trip to New Orleans. I have family history there, and she wanted me to learn more about it.” Boop. She rang the water bottle through, a strange expression on her face. Ernie noticed that she hadn’t smiled back at him, and wondered if she was feeling alright. He felt it would be imprudent to bring this up, so he awkwardly tried to keep the conversation light.

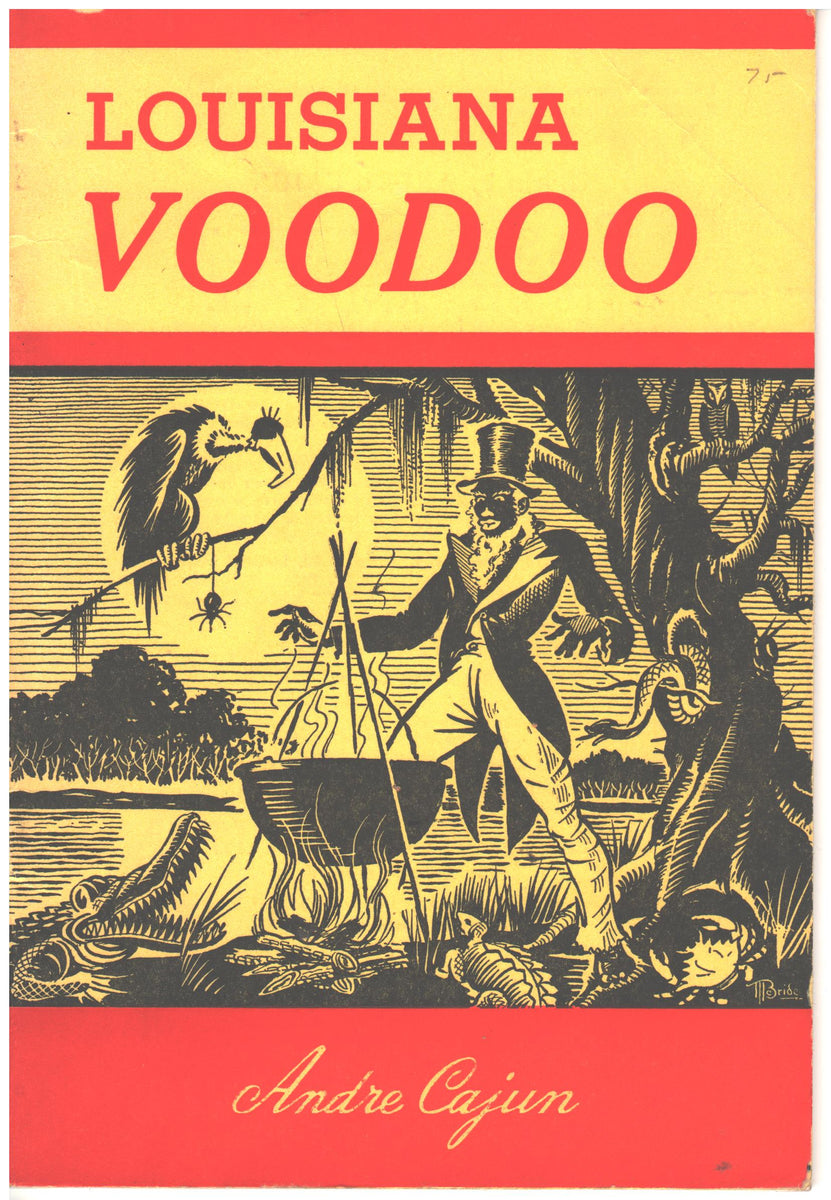

“Did you learn about, uh… voodoo and Mardis Gras and the French?” Ernie said, suddenly aware of how little he knew about New Orleans.

Kitty laughed and took the dollar bills from him. “I learned some of that. Your wife knows a bit about voodoo, she’s saying. Maybe that’s why I can see her.”

Ernie thought back to when his wife had bought all those books on voodoo culture in New Orleans. She had always picked up strange books, getting hooked on one subject or another for weeks. Ernie preferred his old-fashioned murder mysteries. He remembered sitting in the living room with a blanket over both of their legs, reading on the couch together with the radio tuned to the oldies station. “What else did you learn?” he asked, wondering if she could point him toward a voodoo book his wife might have read.

Kitty frowned again, staring at the money he’d handed her. “I learned a lot from my ancestors,” she said simply. Ernie took this to mean that she’d spoken with her dead relatives. That was enough to make anyone melancholy, especially knowing they could never fully come back to life. It was how he felt leaving Walmart—like he was losing his wife again. He always prolonged his conversations with Kitty just to be with his wife a little longer.

Seeming to shake off whatever melancholy memories had intruded upon her normally cheery demeanor, Kitty glanced behind Ernie’s shoulder where his wife usually followed. “Your wife certainly wants you here for a reason.”

“At the supermarket? But we’ve always gone to Ziggy’s.”

She just shrugged and dropped the coins in his hand. Then she plucked the receipt from the printer and handed it over without an explanation. She knew now to throw the coupons away.

“Why did my wife want me here?” Ernie tried again.

Kitty held her breath for a moment to listen to something he couldn’t hear, someone he couldn’t see, but he could feel his wife behind him. Finally. He closed his eyes as the invisible hand touched his shoulder, resting his own hand on the empty spot. “She won’t tell me.”

That sounded just like Ernie’s wife. She was stubborn, always wanted Ernie to figure out what lesson she was trying to teach him. But she was dead, what lesson was he supposed to learn from her now? If he didn’t figure it out, he would hear no end of it in the afterlife.

An impatient “ahem” cut into their conversation. A mother with a sleeping baby stood behind him in line, waiting for Kitty’s cashiering services. She gave Ernie a look that told him she’d overheard the conversation. She was looking between the two with annoyance and skepticism, seeing just another crazy old man and a too-friendly cashier.

And as much as he wanted to grumble something rude about the mother, Ernie instead mimicked Kitty’s shrug, although he ended up looking like he was twitching and abandoned the effort. “I suppose I’ll have to keep coming back until I figure out what she wants,” he said to Kitty in a loud whisper.

The cashier smiled easily. “I suppose so, Ernie.”

Then Ernie laughed, wheezing ever so slightly, and the hand on his shoulder squeezed tighter. He left the supermarket and the impatient lady behind, smiling as he went. Ernie drank the bottle of water, recycling it once it was drained. He decided that when Addie and Jane visited, he would make the best chocolate budyń they’d ever tasted, even if his wife refused to help with the recipe.

Two months before the wedding, Ernie was planning a big meal for Jane and Addie’s arrival. He’d invited his other daughters and the grandchildren, so he knew he needed a lot of food. Determined to make a delicious and traditional Polish meal, Ernie headed to Ziggy’s to get all of the ingredients and spices he needed. He’d been going to Ziggy’s on Wednesdays, as usual, and Walmart on Sundays, for anything he “forgot.” And Ernie had conveniently forgot to buy mushrooms for his potato pyzy stuffing. On Sunday, he grabbed the book he’d found in his wife’s nightstand drawer and headed out.

As Ernie wandered through the Walmart aisles full of colorful cans and boxes and sale signs, some of the regular workers greeted him with a “Hello, Mr. Kowalski!” or “What’s up, Ernie?” and he couldn’t help but walk with a jaunt. He felt his wife walking on his heels, about to step on his shoe. Ernie found a package of fresh mushrooms and made his way more quickly to the checkout lanes, seeking out Kitty. He’d come to think of their exchanges as free psychic therapy, if such a thing existed.

Ernie spotted Kitty leaning against the counter at her register, speaking animatedly with a girl about her age. Three other people were in line, and even though other lanes had fewer people, Ernie was glad to wait. He even chatted a little with the man in front of him who was buying a gigantic bag of dog food. The man showed Ernie pictures of his dog, a Mastiff named Tinkerbell. Ernie was still chuckling about the dog’s name when he made it to Kitty’s register. Though Ernie imagined that Kitty must be tired after so many customers, she still greeted him with a cheery, “How are you, Ernie?”

“Wonderful,” he answered, handing her the mushroom package. “I’m meeting my daughter’s fiancée tonight.”

“Oh?” The loud boop no longer jangled Ernie’s nerves.

His wife’s hand appeared on his shoulder, and Ernie instinctively rested his own hand in the same spot, pretending he was holding his wife’s hand there. “Yes, I’m making dinner.” Ernie was getting a little impatient, hoping that Kitty would tell him about his wife—that she approved of his dinner plans, that she was finally going to reveal the secret to her chocolate budyń.

The cashier’s eyes flickered to the space behind Ernie like she’d heard his request. “She’ll be there with you. Don’t worry.” Kitty hadn’t answered any of his questions, but somehow it was the answer Ernie needed.

Ernie then slipped a paperback book out of his back pocket and set it next to the cash he set down. “I found this book of my wife’s. About voodoo,” Ernie said, wondering if it was odd to give gifts to a cashier—or a psychic. Kitty picked up the book with both hands and studied the strangely dressed woman on the cover. Then, noticing the line forming again behind Ernie, Kitty set the book down and retrieved Ernie’s change from the drawer. She then nodded toward where his wife’s spirit lurked. “Thank you.” Then she turned back to Ernie, dropping the cash and coins into his hand. “Good luck at dinner, Ernie.”

But Ernie knew he didn’t need luck. If his wife was watching while he made the budyń, she wouldn’t let him get it wrong. Maybe being a crazy old man wasn’t that bad, after all.

-Ryn PB

Author’s Note: This is an older story from two or three years ago. My computer broke and I didn’t have it for over a week, plus a couple other boring excuses, but the point is that I didn’t write anything new for today. So I hope you enjoyed this one, even if it’s not super new. And happy belated Valentine’s Day!