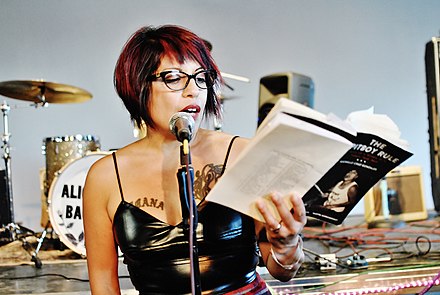

Michelle “Todd” Cruz Gonzales claims that her journey from punk rock drummer to college English professor was not all that far-fetched. For a Xicana from a small town who taught herself how to drum and started her own hardcore feminist band, perhaps nothing is too far-fetched. However, she was not always so comfortable reconciling different aspects of her identity.

Born in East L.A. in 1969, Gonzales was raised in the small town of Tuolumne by a single mother. In this town, she bonded with two high school friends over being raised by single mothers on welfare, and they ultimately decided to start their own punk band when they were fifteen, calling themselves Bitch Fight.

Through the patience of a friend’s mother, Gonzales’s interest in politics grew and her understanding of the news increased, sparking her desire to bring political topics into her lyrics like the Clash, one of her favorite bands, had done. The three young women moved to San Francisco to integrate themselves into the Bay Area punk scene. Soon enough, though, Gonzales realized these girls were not serious about the band and went on to search for other women to be in a hardcore feminist band, Spitboy, named after an alternative creation myth in which a woman put all of her hatred, judgment, etc. into her spit and that spit created a boy.

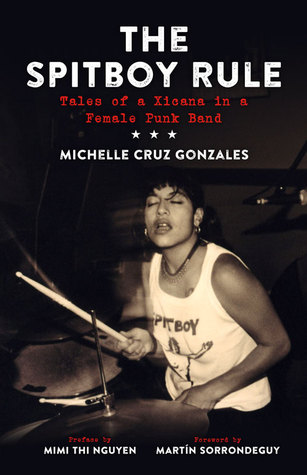

Inspired by Alice Bag’s book Violence Girl and the lack of Xicana narratives in punk history, especially because punk feminist history is overtaken by the mainly white riot grrrl movement, Gonzales wrote the book The Spitboy Rule about her experience as a largely invisible Xicana in the ’90s punk scene.

Starting in 1990, Gonzales broke through in the punk scene as a talented drummer and songwriter in the band Spitboy, an all-female hardcore feminist punk band. Unfortunately, she found difficulties reconciling this punk drummer identity with her Xicana identity. In the punk scene, one’s affiliation with their band is more important than one’s family ties. Because Gonzales was going by the nickname “Todd Spitboy,” her name was erased, and therefore part of her identity was erased.

When the band released their third 7-inch record, “Mi Cuerpo Es Mío,” a white riot grrrl accused the band of cultural appropriation, signaling to Gonzales that her “body was invisible” (Gonzales 87). In a scene that she tried so hard to fit into, Gonzales felt discontented with the erasure of her Xicanisma. “In conforming to the nonconformist punk ways, adhering, mostly, to the punk uniform, I had lost something along the way, and I began to experience rumblings … I knew that my identity was the root of my confusion and discontent, so I began taking Spanish classes at a local community college…” (Gonzales 89).

Another part of her journey to accept the Xicana part of herself was suggesting a Spanish title for this LP, but that white riot grrrl managed to taint this victory. Even people at shows would comment that they had no idea she was Xicana; they just thought of her as the Spitboy drummer. “At shows, I did not register as a Xicana. I was just the drummer of Spitboy, and for some reason I couldn’t be both” (Gonzales 90).

Gonzales felt this alienation most acutely when touring outside the Bay Area. She discusses feeling this loneliness while on tour, maybe more-so than her bandmates. She often found herself alone in the van with a book or journal, feeling like her bandmates would not understand her alienation. She stayed quiet when she wanted to speak up because she knew they would not completely understand. “Since I was what people still called a minority in both the punk scene and in America, and maybe because I was still young, I didn’t feel like I quite fit in anywhere. Perhaps I thought being in a band, being a part of the scene in this central way would fix that feeling, but it never did…” Gonzales still found ways to cling to her Latina and Xicana identity. While visiting Australia, she had a fling with a Latina punk who came to Spitboy shows, she often kept a “book from home by some Latina author in my bag,” and she listened to Linda Ronstadt during moments of discontent (Gonzales 89, 103, 106).

In this venture, Gonzales also took her bandmates to visit her grandma in East L.A., but this ended up backfiring on her. Her bandmates, all white women from fairly well-off families who were usually friendly, acted quiet and awkward in the house. “A tough old broad, [my grandma] speaks with an accent, speaks and cusses in both English and Spanish…” (Gonzales 48). Gonzales thought her friends would enjoy her grandmother, a strong woman with a difficult background and someone Gonzales looks up to, but they disappointed her.

“I had made everyone uncomfortable, and now I was outside of my body, seeing my adored Grandma and her shabby East LA home, which I had always found tidy and comforting, her knickknacks, … and all her family photos of Mexicans, and now myself through different eyes, and I didn’t like it one bit” (Gonzales 50). Her bandmates do not understand why Gonzales’s mother would have a child with three different men or why Gonzales’s grandma would live in a cluttered home.

Instances like these make Gonzales feel “trapped in anger” with a “cancer of silence” growing inside her (17, 125). Anzaldúa often discusses the idea of “Coatlicue states” in her novel Borderlands/La Frontera, and this anger and silence is the version of the Coatlicue state that Gonzales was learning to push through during her time in Spitboy. “Only part of me was part of something” (“Michelle Cruz Gonzales…”). She no longer wanted to feel complicit in her invisibility, but instead become visible in her own way, which is why she began learning the Spanish language.

Not only did Gonzales have to deal with the invisibility of her body and skin, she also had to deal with the intense sexism in the punk scene. After being bullied by teachers and students all throughout school for her skin, Gonzales wanted to fit in in the punk scene, but it is hard to fit in when you’re in an all-female hardcore punk band that sings about feminist issues and denies the label “riot grrrl.”

This controversy about not being riot grrrls did not become a huge issue until Spitboy toured in the D.C. area, where riot grrrls were a big movement. When asked if Spitboy would make men stand in the back as riot grrrl bands often did at shows, Gonzales announced to the crowd that the men did not need to stand at back because they were definitively not a riot grrrl band. All four “Spitwomen” had decided not to be a riot grrrl band because they were against sexism, not against men.

Later on in her life, Gonzales realized her personal aversion to the riot grrrl movement may have been because it was a white-washed version of punk feminism (“Michelle Cruz Gonzales…”). Even though Gonzales found it hard to speak up about her race in the midst of 1990s “colorblindness,” her bandmates had her back and would sometimes pick up on her discomfort. They may not have understood her background, her aversion to hugging strangers, or her feelings of invisibility, but they understood the threats women faced walking down the street and the lack of support available after experiencing sexual harassment. They performed the songs “The Threat” and “Seriously” about these issues together night after night. The other Spitwomen respected Gonzales for her drumming and lyrics and feminism, but not for her Xicanisma.

Unfortunately, the discord between her two main identities continued on throughout her time with Spitboy, coming to a head during the band’s 1995 Pacific Rim tour during which Adrienne, the lead singer, decided to leave the band. Tensions had been rising in the band, and Gonzales admits that she may have taken out her anger on her bandmates while she was going through her “hating white people phase,” which she deemed necessary to break through that Coatlicue state of anger and silence (“Michelle Cruz Gonzales…”).

When Spitboy ultimately decided to collaborate with Los Crudos, an all-Chicano punk band, on an album called “Viviendo Asperamente,” Gonzales felt a sense of personal validation that went beyond just making good music; her bandmates finally saw her. “The title Viviendo Asperamente, or ‘roughly living,’ seemed to capture the content of songs by both bands—Latino struggles and feminist struggles, living with such awareness was often abrasive, hard, rough” (Gonzales 117).

Dating the guitarist of Los Crudos was the first time she allowed herself to date a Latino man, having avoided it because of her mother’s bad experience with Gonzales’s father. Years later, she married her Latino husband Inés and took him to see Los Crudos perform, but that was the last time she stepped foot in 924 Gilman, a popular East Bay punk venue, for thirteen years. “The punk scene’s enthusiasm for Los Crudos was for me, and probably many others, an indirect form of personal validation. But the scene, like America, could only change so much so fast, and I didn’t have the time or the patience to wait around and endure both” (Gonzales 119). This distance allowed her to pursue other arts like writing and teaching.

After Adrienne left and Instant Girl, the Spitboy derivative band involving the three remaining members, dissolved, Gonzales decided to go to school full-time, instead of part-time like she had been doing for ten years. Finally able to overcome her fear of the daunting government forms and high tuition rates, she applied to the all-women Mills College. With a scholarship to help on the financial front, Gonzales went all the way through undergraduate and graduate school with degrees in English and creative writing and a minor in ethnic studies.

Because she was raised by strong women and surrounded herself with strong women in the punk scene, Gonzales wanted to go to an all-female school to continue getting educated by women. After school, she went straight into her career as a professor, eventually ending up at Las Positas Community College because “community college is, like, totally punk” (“Michelle Cruz Gonzales…”).

Gonzales continues to be a punk rock professor, playing drums in the Las Positas English Department band “Rawk Hawks,” who sing parodies of pop songs about budget cuts and grading papers. She works with the school’s Puente Project, which connects disadvantaged students with mentors and counseling programs.

When asked why she switched from punk rocker to English teacher, Gonzales simply said, “I knew I needed another art form, another outlet. If I could teach, my art would continue” (Ruggiero). Being a teacher feels similar to being in the punk rock scene to Gonzales because she gets to interact with young people and exchange ideas, which she spent a lot of time doing as a punk.

As a lyricist, Gonzales has always considered herself a writer, and with this memoir, she is now a published author. This is the second memoir she has penned, though the first to be published. Her first memoir is about growing up Xicana in a small town, but The Spitboy Rule found an audience much faster.

Currently, Gonzales is teaching English and creative writing at the community college, working with activism on campus, and penning a satirical, dystopian novel about forced intermarriage between white and Latine/x people.

Though her students may not all know who she once was, drummer and punk extraordinaire Todd Spitboy, Gonzales teaches everyone what she learned during that time: “We are all of our identities all the time—we can try to compartmentalize them, but that only works for so long” (“Forgotten Women…”). A mother, a drummer, a teacher, a student, an activist, a woman, a daughter, a wife, a punk, a Xicana—Michelle Cruz Gonzales embodies them all fully.

Resources

Gonzales, Michelle Cruz. “The Forgotten Women of Punk: Spitboy’s Michelle Cruz Gonzales on Riot Grrrl, Dystopias, and More.” Interview by Tom Hawking. Flavorwire, 4 August 2015.

Gonzales, Michelle Cruz. “Michelle Cruz Gonzales: The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band.” Interview by Richard Schur. New Books Network, 12 August 2016.

Gonzales, Michelle Cruz. The Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band. Oakland, PM Press, 2016.

Ruggiero, Angela. “From punk to professor: Livermore teacher details journey in new memoir.” The Mercury News, Bay Area News Group, 3 March 2017.